When I was 17 years old I drove my small car onto an off ramp for a highway in Michigan. When I came upon the intersection of the ramp and the road onto which I had intended to turn, I was faced with the all too common situation of having a large truck to my left, which obstructed my view of the road, and traffic. Naively, I trusted in the judgment of the truck driver who waved me into the intersection. While I was in no position to see the traffic on the road, there was no question that the truck driver was in such a position to do so. Moreover, it was unequivocally clear that the driver was directing me into the intersection. Much to my horror, once I entered the intersection I discovered that I had pulled out right in front of a motorcyclist. But for my quick reaction to pull onto the shoulder of the road and the motorcyclist’s ability to react a great tragedy might have occurred that day. Nevertheless, the motorcyclist, and understandably so, displayed a few of the universal gestures for his displeasure with me. Needless to say, I learned my lesson and will never again be so foolish as to trust in the judgment of another driver despite his vantage point.

Perhaps it is due to this experience that I so clearly see the Indiana Court of Appeals decision in Key v. Hamilton as the right decision. This past month, the Court of Appeals handed down their decision holding that a truck driver who waved a car into an intersection was liable to a motorcyclist who struck the car when it pulled in front of his motorcycle.

As the case was one based in negligence, the plaintiff, the motorcyclist, was forced to prove that not only did the driver of the car breach his legal duties to the motorcyclist, but so too did the truck driver. The primary issue of the case was the determination of whether the actions of the truck driver to wave the car into the intersection resulted in the assumption of a duty.

A quick overview of Indiana law on assumption of duty. It is generally true that you have no duty to help anyone who you did not put in a position of peril. This is most clearly seen in the situation where a man is walking on the beach and sees a woman drowning. The law does not hold the man on the beach liable for allowing the woman to perish. However, the second that the man on the beach goes to aid the drowning woman, he assumes a duty to act with reasonable care and to not negligently injure the person he is trying to rescue. This standard makes sense. The law is not going to require a person to put his own life at risk for another with whom he has no prior relationship. However, if that person does decide to take on that risk, it is in everyone’s best interest that the man’s actions are not such as to cause more injury to the person than if he had done nothing at all. Now, mind you, this does not mean that just because the man on the beach tried to help the drowning person and was unable to save her that he is liable for her death. The man did have to be negligent in order to find himself liable.

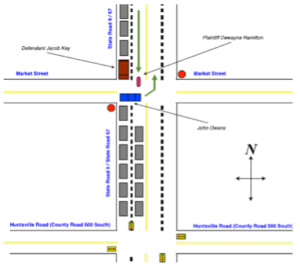

With that in mind, let us turn to the specifics of Key v. Hamilton. Below is the image of the scene of the accident that was added to the Court of Appeals’ opinion. It depicts the plaintiff motorcyclist heading south in the lane adjacent to the defendant truck driver. In blue you can see the car that was waved into the intersection in front of the motorcyclist.

Because the issue in the case was not whether the driver of the car was negligent – the jury found the driver of the car 50% responsible for the collision – but whether the truck driver was negligent, the Court of Appeals had to determine whether the truck driver owed a duty to the motorcyclist to act with reasonable care. As a general rule, the duty to act with reasonable care is owed only to those who are reasonably foreseeable as victims of the failure to act reasonably. In this situation, the Court of Appeals determined that the injuries to the motorcyclist “were not only a natural consequence” of the truck driver’s negligence, but that “they were also foreseeable as a result[.]”

As such, the Court of Appeals held that the truck driver assumed a duty to the motorcyclist when he acted to wave the car into the intersection. Therefore, by failing to act reasonably so as to determine that it was safe for the car to enter into the intersection, the truck driver was liable for the personal injuries to the motorcyclist including his lost wages, medical care, permanent injuries, and his pain and suffering.

The decision by the Court of Appeals, while sufficient to create binding precedent, was not unanimous. One of the three judges, the Honorable Judge Mathias, disagreed with the majority opinion. Judge Mathias did not believe that Indiana law ought to recognize a duty where a driver, such as the truck driver, stops his lane of traffic and waves a vehicle into an intersection. Judge Mathias believed that the public policy concerns of such a decision were perhaps the greatest threat to finding a duty. He argued that the courtesy of yielding to other drivers is commonplace in Indiana and something in which Hoosiers ought to take pride. He feared that to find an assumption of duty for such a kind and courteous act would provide a chill on politeness in vehicle operation perhaps resulting in greater incidents of road rage.

I cannot agree with Judge Mathias’ view. First, I believe that recognition of such a duty will have the effect of causing persons in the truck driver’s position to act more reasonably in ascertaining whether there is a danger for the vehicle entering the intersection. The likely effect would be to cut down on the number of incidents in which a person, absent mindedly signals to a driver to enter the intersection before performing a sufficient inspection to make sure that it is safe.

Second, as Judge Mathias so aptly notes, Hoosiers are known for their courteousness, indeed, almost to a fault. I am not advocating that Hoosiers lose our Midwest generosity and charm, but rather exposing a situation in which the polite nature of us Hoosiers can result in serious injury. On first glance, the driver yielding his space in the road is the only one acting politely. However, consider what would happen if the driver wanting to enter the road were to not accept the polite gesture of the driver yielding the road. If the driver who wanted to enter the road knew that the sole risk for determining whether it is safe to enter the road was upon him, then he would be less apt to do so. The driver yielding the road would feel offended and may become more likely to suffer from road rage and less likely to yield the road in the future. Or worse yet, out of a sense of obligation to the polite and courteous order of Hoosier society, the driver might feel compelled to enter the intersection without regard for his own well being in order to not seem rude. I believe that Judge Mathias has reasonable fears of the chilling of the common courtesies of operating on Indiana roads. However, I do not believe that the Judge has fully explored the situation.

Some commentators such as Jenny Montgomery in her March 14 piece in The Indiana Lawyer contend that Key v. Hamilton may well be limited to one unique fact in the case. In the case the majority opinion seemed to give sizable weight to the fact that the truck driver “was not just sitting in his truck” but rather, he “got out of his truck, stood on the doorsill, and examined the traffic situation behind him.” Indeed, the majority opinion states, “The commonly used courtesy wave will never be sufficient to create a duty on the part of the signaling driver.” Were the opinion in this case to be confined to the facts and provide only a duty where the driver took such extreme and visible measures to ascertain the traffic situation, I believe a great injustice would occur.

On this point, Judge Mathias and I are in complete agreement. In his dissenting opinion Judge Mathias contended that to rely upon the actions of the truck driver getting out of his vehicle and surveying the area to be the sole basis for finding a duty is to lead to an unjust result. Judge Mathias found that to hold this truck driver liable where others who simply wave a car into the intersection have no such duty is to penalize a driver who has done more to insure the safety of the other drivers. On this point I could not agree more with Judge Mathias. To determine that this case does not have great applicability going forward is to create an extremely unjust result for the truck driver. Put simply, the danger in the case is not its decision but is to narrowly constrain it for future use.

While the Court explicitly states that the courtesy wave alone is never sufficient to create a duty, I think it to be short sighted for a court or anyone else to interpret this language as meaning that a duty is only formed when the signaling driver takes such extreme measures as the truck driver did here. It is my reading of the opinion that the Court has left open for future analysis the issue as to whether the position of the signaling driver, especially if that driver is in a higher elevated vehicle, is sufficient to create a duty.

In my opinion, as both a practicing lawyer who works to preserve the rights of injured persons through all forms of actions including class action and mass tort cases as well as a person who has operated vehicles on Indiana’s roadways for many years, there is no question that a driver signaling another driver into an intersection is assuming a duty by doing so. The person who, like the truck driver in Key v. Hamilton and like the truck driver when I was 17, waves another into an intersection is making an affirmative assertion that he or she has a better vantage point from which to see traffic and that it is safe for the other driver to pull into an intersection. It is just like the man walking on the beach. While the law cannot require him to rescue the drowning woman, if he tries to help her he needs to not injure her worse than if he had simply stayed on the beach. So too must a driver who is in a position to wave to another vehicle and in so doing indicate that he has a superior vantage point not do so to the harm of the driver he is trying to help. If a driver does wave a car into the intersection and his actions directly cause the harm, then he should be responsible for all of the foreseeable injuries that his actions have caused including the medical expenses, lost wages, and all other injuries required by justice. Think of it like this, had the truck driver never waved the car into the intersection the motorcyclist would never have been injured. That is the singular moment of the entire case and it is my opinion and the opinion of the majority for the Indiana Court of Appeals that the truck driver is legally responsible for his actions.

Sources

- Key v. Hamilton, 963 N.E.2d 573 (Ind. Ct. App. 2012), trans. denied.

- Jenny Montgomery, Tort Law Case Tests Boundaries of ‘Duty’, The Indiana Lawyer, Vol. 23, No. 1, at 1 & 19.

*Disclaimer: The author is licensed to practice in the state of Indiana. The information contained above is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any subject matter. Laws vary by state and region. Furthermore, the law is constantly changing. Thus, the information above may no longer be accurate at this time. No reader of this content, clients or otherwise, should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any content included herein without seeking the appropriate legal or other professional advice on the particular facts and circumstances at issue.

Class action lawsuits for construction contractors who were overcharged by ready mix concrete suppliers due to price-fixing conspiracy.

Settlement for the widow and surviving children of a man who died due to negligence.

Settlement for a woman paralyzed from the waist down in a car collision.

Achieved the state's maximum settlement amount in a medical malpractice case for the widow of man who died due to doctors' negligence.

Settlement on behalf of a business partner who was forced out of his company.

“The team at Pavlack Law, LLC, LLC was professional, loyal, and hardworking from beginning to end. Even when I didn’t know if I had a case, they were extremely helpful and demonstrated their expertise from our first consultation all the way through trial.”

“Eric Pavlack and his associates are a great legal team! Anytime I had questions they were always very helpful and got back to me right away. Throughout the whole process they made sure I was comfortable moving forward with each step. I recommend Pavlack Law, LLC, LLC to anyone looking for legal representation.”

“Attorney Pavlack has represented me and my family for years in various cases including Title Insurance, Wills, General Legal Matters and Social Security. He is always efficient and willing to work around our busy schedules. Highly recommended.”